1822 – Anton Karl Freidrich Struckmeier

Anton Karl Freidrich Struckmeier was born on December 17, 1822 in a tenant farmer’s house near the Struckmeier farm at Hof number 16 in the village of Holsen to Georg Heinrich Gottlieb Struckmeier and Anna Marie Elisabeth Cassebaum.

Holsen was located in the Schnathorst kirchspiel (Schnathorst parish) of Kreis Lübbecke (Lübbecke county) of Provinz Westfalen (the Province of Westfalen), which was a part of Königreich Prueßen (the Kingdom of Prussia). Friedrich Wilhelm III was the könig, or king, of Prussia at the time of Karl’s birth. Königreich Prueßen was a leading state in the Deutscher Bund or German Confederation which had been formed in 1815.

Anton Karl Freidrich Struckmeier was baptized the day he was born in the neighboring town of Schnathorst, where the parish church was located—the Evangelische Kirche Schnathorst (Evangelical Church of Schnathorst). Throughout his life, he was known by his second given name—Karl—a trait that was not unusual in the Struckmeier family.

The baptismal record indicates that Karl was born at “Holsen bei,” meaning near Holsen. In 1836, his mother died at “Holsen bei Nr. 16,” meaning near house number 16. Christine Honermeyer, a member of the Hüllhorst genealogical society, informs me that this would indicate their residence was a nearby tenant farmer’s house and not the main farm house.

the name ‘Struckmeier’

The Struckmeier or Struckmeyer name derives from two words. The word struck is a variation of strauch which is a shrub or bush. A meier was the term for a farm manager on an estate. Sometimes it is translated as a farmer, but the typical German word to describe a farmer is bauer, or sometimes colon. As surnames developed in the Middle Ages, they sometimes reflected a person’s occupation, or location, or both. Struckmeier may refer to the manager of a farm in a grassland near the woods. Just north of Holsen is a low mountain range known as the Wiehengebirge which is covered with an oak and shrub forest. The spelling of the name varied in different records, usually Struckmeier, sometimes Struckmeyer, and even Strukmeyer or Struckmÿer.

the Struckmeiers of Holsen Hof Number 16

As far as I can tell at this point, all of my Struckmeier ancestors had their roots in the village of Holsen. Karl Struckmeier was born there near Hof Number 16 in 1822. The term hof refers specifically to a courtyard or garden, but is often used to refer to a rural home and farm.

Through church records, we can trace Karl’s lineage back four more generations to about 1697. Karl’s father was Georg Heinrich Gottlieb Struckmeier, born in 1791 in Holsen. When he married, he was living near Hof #10. Georg’s father was Johann Jürgen Struckmeier, born in 1754 in Holsen. His father was Henrich Hermann Struckmeier born in 1728 in Holsen #16. Finally, his father was Henrich Jürgen Brinkhoff (also in records as Nieder-Brinkhoff and Nedderbrinckhoff) born in 1697 at Hof #9 in the neighboring town of Nieder Brinkhof (Lower Brinkhof).

This is where German genealogy gets interesting. Henrich Jürgen Brinkhoff married Catharina Margaretha Struckmeyer. Because her family had property (the farm and house at Holsen #16), he took her last name in marriage. This practice was not unusual at the time; the common term was “marrying the farm.” Thus his children were named Struckmeier, not Brinkhoff. Through Catharina Struckmeyer we can trace the Struckmeier family at Holsen #16 back three more generations to Johann Struckmeier (or Struckmÿer), born about 1610 and lived in Holsen #16.

All of these Struckmeier ancestors were most likely baptized in the parish church in Schnathorst where the records date to 1714, but no earlier. Without additional church records, it is difficult to trace the family back any further, although property tax records for the farm at Holsen have revealed additional information about the owners. The Struckmeier farm at Holsen #16 is documented by land registries as far back as 1646.

Holsen Hof #16 (shown above) was rebuilt in 1878 as indicated by this inscription over the current farmhouse’s entrance.

Translated, it reads: “Anton Heinrich Struckmeier and his wife Anna Marie Struckmeier born Düker in Nr. 1 Ahlsen and Karl Struckmeier built this house in the year 1878. Me K. Büner.”

The grave marker of Anton Heinrich Struckmeier (1833-1913) and Anna Marie Luise Düker (1835-1898) is prominent in the graveyard of the church in Schnathorst. The final part of the inscription reads “and their nine children.”

Anton Heinrich Struckmeyer was a first cousin to Anton Karl Freidrich (Karl) Struckmeier. Karl’s father, Georg Heinrich Gottlieb Struckmeier (1791-1854), was the older brother of Anton Heinrich’s father, Hinrich Hermann Struckmeier (1797-1879).

I was contacted in May 2011 by Gerda Homann Peterson who grew up in Schnathorst and now lives in the United States. She has a copy of a 720-page book titled “Seit 1425 Kirchengemeinde Schnathorst” (Schnathorst Church Parish Since 1425). The book includes a photo of Holsen #16 and states that in tax records from 1717 the owner of the Struckmeier farm in Holsen was catagorized as a Viertel meier or ‘quarter farmer’, or perhaps more accurately as a ‘quarter farm manager.’ According to Gerda, the size of the farm plus the number of horses determined how much revenue a farmer had to pay the ruling authorities, both secular and religious. The Struckmeiers are listed as having two horses making the property a Viertel hof or ‘quarter farm’ for tax purposes. A Vollmeier or ‘full farm manager’ had at least 6 horses on a Voll hof or ‘full farm’.

Erhard Struckmeier, who lives in Bünde, Germany about eight miles southwest of Holsen, is also a descendant of the Struckmeiers of Holsen #16. He has found land registry records from 1682 and 1646 that document the names of Struckmeier ancestors in the Holsen farmhouse and his research has been instrumental in identifying the genealogy prior to 1714 when the church records began.

Our common ancestor is Henrich Hermann Struckmeier (1728-1808) who was married three times and had 16 children. Erhard’s family is descended from Henrich’s third wife, Anna Marie Ilsabein Wielen (1759-1815). Our family is descended from Henrich’s first wife, Katharina Maria Meier (1731-1764).

Today, Holsen #16 is owned by the Rösener family as indicated by the legend of the photo at the right which appeared in the Schnathorst church history. Translated, it reads “Rösener, formerly Struckmeyer, Holsen Nr. 16.” In 1926, Louise Marie Struckmeier married Christian Heinrich Wilhelm Rösener and the name Struckmeier was no longer identified with the property. Prior to the name change, the Struckmeier family may have occupied the land at Holsen #16 for over 300 years.

The current address is Holsener Straße (Strasse) 142, 32609 Hüllhorst, Kreis Minden-Lübbecke. The current owner is Dirk Rösener, a shepherd who raises organically-fed sheep on the edge of a large protected peat bog between Minden and Lübbecke.

The house numbers in the German villages and countryside originated from Urbar documents, which were registries of cultivated land used for taxation purposes. The number for the Struckmeier house in Holsen first appeared in the Urbar of 1717. Prior to that, the farm was referred to by the name of the farmer and the estate of the nobleman to which the land belonged.

For example, in 1646, the Urbar identifies Johan Struckmÿer, who lived and worked on a Quarter Farm belonging to a nobleman named Groß Eickelde (or, in other documents, Groß Eickel). The term groß (or gross) means large or great and was probably used to differentiate two estate owners of the same name, one who had a large estate, Groß Eickelde, and another, Klein Eickelde who had a klein or small estate. It could also refer to brothers—an elder (Groß) and a younger (Klein). In 1646, we are clearly still in the feudal system with serfs and peasants working in the medieval manor for noble landowners. Thus, the earliest Struckmeiers in Holsen farmed and managed land which they did not own. The Struckmeiers were “Liebeigenen” or serfs in a system known as “Leibeigenschaft.”

Swedish troops had occupied the ancient city of Minden and the surrounding area in which Holsen is situated from 1634 to 1650. King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden had invaded the Baltic and North German states in 1630 in the midst of the Thirty Years’ War. A peace treaty was eventually signed in 1648, but in 1646 the Swedes were making preparations to firmly establish the Minden region as a Swedish province and accordingly conducted a census of the local farms and towns to establish a new taxation record for the coming years. Thus the Urbar of 1646.

Westfalen today

Today, Holsen, Hüllhorst, and Schnathorst are in the German Bundesland (state) of Nordrhein-Westfalen (North Rhine-Westphalia) which lies in the western region of Germany and is bordered on the west by the Netherlands and Belgium. To the north is the state of Lower Saxony.

Within the state are five Regierungsbezirke (administrative districts)—Köln (Cologne), Düsseldorf, Münster, Amsberg and Detmold.

Holsen lies in the Detmold district, which is in turn divided into six Kreise (rural counties). Kreis literally means a ‘circle’. The furthest north is Kreis Minden-Lübbecke. The territory of the modern county is roughly the same as the ancient Hochstift Minden or Bishopric of Minden which was founded by Charlemagne in 803 after he had defeated the Saxon tribes in the area.

This county is sometimes known as Mühlenkreis (the Mill County) because of the great number of historic mills there—wind, water, and horse-driven. A driving route through the region, the Westfälische Mühlenstraße (Westfalen mill road), passes 40 different mills.

The current county of Kreis Minden-Lübbecke was formed from a merger of the counties of Minden and Lübbecke in 1973. But in the nineteenth century, Karl Struckmeier lived in Kreis Lübbecke, part of the Prussian province of Westfalen.

Kreis Lübbecke

The rural county of Kreis Lübbecke had been formed in 1816. The original seat was in the town of Rahden which lies about ten miles north of Holsen on the north side of the Wiehengebirge mountain range. In January 1832, the seat moved south to Lübbecke, about three miles north of Holsen, still on the north side of the range.

The town of Lübbecke, seen in the picture to the right, is renowned for its breweries, including Barre Bräu (founded in 1842), and is known for its beer fountain which flows during local festivals.

In 1822, the year Karl Struckmeier was born, Kreis Lübbecke had 33,763 residents in its boundaries. In 1852, the year his son Ludwig was born, the population had grown to 50,249. And in 1871, just before the family emigrated to the United States, Kreis Lübbecke had decreased to 47,593 people.

A century later, in 1973, the county was merged with Kreis Minden to become Kreis Minden-Lübbecke. The last council leader of Kreis Lübbecke before the merger was Hermann Struckmeier (May 9, 1920 – February 5, 2009) who led the council from 1969 to 1972. Hermann was born in Schnathorst #78 and lived in the town of Hüllhorst. In 1973, he became the first governor of the newly formed Kreis Minden-Lübbecke, and served as its leader until 1984. I have no information about a direct connection between our family and that of Hermann Struckmeier, although he once told Erhard Struckmeyer that there may be a link between the families originating in Holsen #3. Perhaps there is more to come regarding this.

When Karl Struckmeier married in 1850, he moved from Holsen to the neighboring town of Hüllhorst, about a mile to the southwest, where his new wife’s family had a farm. So three neighboring villages—Holsen, Schnathorst, and Hüllhorst—are central to the story of the Struckmeier family in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The three villages form an elongated triangle, with Holsen at the northern apex and at a higher elevation. The road between Hüllhorst and Schnathorst, which forms the bottom of this triangle, is called Schnathorster Straße. As seen in the photo below, they all lie on the southern side of the low wooded Wiehengebirge mountain range.

Holsen

The small farming village of Holsen is situated on the southern slope of the Wiehengebirge (the Wiehe mountains). The name Wiehe comes from Old Saxon and means ‘sacred mountain’.

The mountains stretch along a curving east-west axis beginning at the Weser River near Minden (to the east of Holsen) and terminating in the vicinity of Osnabrück to the west. The highest elevation is 320 meters (1,049 feet). The photo at the right shows the view of the mountains from Holsen.

Farmers in the area of Holsen often raised wheat, oats, peas, turnips, and potatoes. By the middle of the nineteenth century a majority of the population also grew flax which was spun and woven into linen cloth as a cottage industry.

In 2010, Holsen celebrated its 750th anniversary, putting its founding in the year 1260 when it was first mentioned in writing. Today, it has about 1,100 residents.

Schnathorst

The town of Schnathorst is located about a mile to the southeast of Holsen on the plain below the Wiehe mountains.

The first written records for the town of Schnathorst appeared in 1244.

Larger than Holsen, it was the site of the Evangelische Kirche Schnathorst, the Evangelical parish church that served the Holsen villagers. The church dates to 1425 when it was a Roman Catholic parish. During the Protestant Reformation, the church became Lutheran. Church records date back to 1714. Until some time in the nineteenth century, the people of Holsen were required to bury their dead in the Schnathorst parish cemetery, and not in their hometown. Today, the church is Schnathorst Evangelical Lutheran Church.

Although we have not traced any of my direct Struckmeier ancestors to this town, another line of Struckmeiers farmed in this area and lived in houses #16 and #3 in Schnathorst. Those who lived in house #16 were known as the Große (large) Struckmeiers because they owned a large farm. In contrast, the Kleine (small) Struckmeiers in house #3 had a smaller half-farm.

The farm house of Schnathorst #3 is located on the Struckhof farm which lies just to the east of Schnathorst on the road to Minden. Today, this farm is a part of the town of Schnathorst which in turn is a part of the larger Hüllhorst municipality and is the site of the windmill shown at the left which dates from 1797. It is among the oldest and largest mills in Northern Germany.

Hüllhorst

Hüllhorst is about a mile and a half west of Schnathorst and a mile southwest of Holsen on the plain below the Wiehengebirge range. Hüllhorst was first mentioned in written records in 1290.

The town’s coat of arms includes a castle in its imagery. The Reineberg castle once stood north of the town, but was demolished in the 17th century. Reineberg means “Pure Mountain.”

Of the three neighboring villages, Hüllhorst was the largest in the 1800s. It served as the administrative center for a number of neighboring villages—Grossenberken, Oberbauerschaft, Quarnheim, and Tengern in addition to Holsen and Schnathorst.

The meaning of the name “Hüllhorst” is elusive. Computerized translators often translate it as “cladding refuge” or “envelope nesting“. Hülle means a wrapping, cladding, covering, or shroud. It can also refer to a husk. As we said earlier, “horst” could mean a nest, a wooded hill, or a refuge. Perhaps the name means something like covered refuge because it, like Schnathorst, sits just below the shelter of the forested Wiehe mountains.

Westfalen’s early history

The three small towns lie in the larger area historically known as Westfalen (or in English, Westphalia). No consistent definition of borders can be given to this historic region, because the name Westfalen was applied to several different entities throughout history. It is roughly the region in west-central Germany which lies east of the Rhine River, west of the Weser River, and north of the Ruhr River. Westfalen means “the western plain.”

There is archeological evidence of Neolithic settlements in the area, but our earliest knowledge of people in the historical era began about 500 BCE when the region was occupied by various Germanic tribes. The earliest were the Sicambri, Bructeri, Marsi, and Cherusci.

Westfalen was briefly conquered and held held by the Roman Empire over a period dating from 12 BCE to 5 CE. But in 9 CE, the Romans were defeated by locals in the battle in the Teutoburger Wald (Teutoburg Forest), when an alliance of Germanic tribes ambushed and destroyed three Roman legions. The battle began a seven-year war which established the Rhine River as the boundary of the Roman Empire for the next four hundred years. That placed Westfalen outside of the empire’s borders.

The site of the Schlacht im Teutoburger Wald (Battle of the Teutoburg Forest) was about 25 miles west of Hüllhorst and 12 miles north of Osnabrück on a low hill known as Kalkreise. The Teutoburg Forest is the name given to the woodlands that cover the Wiehengebirge mountains there.

Roman historians referred to the battle as Clades Variana, or the “Varian disaster,” a reference to the Roman military commander Publius Quinctilius Varus (46 BCE – 9CE). The victorious Germanic troops were led by Arminius (also known as “Hermann“), a leader of the Cherusci tribe.

As a young man, Arminius (18 BCE – 21 CE) had lived in Rome as a hostage, where he had received a military education. After his return to the region that the Romans called the province of Germania, he was a trusted advisor to the Roman commander Varus. In secret, he forged an alliance of Germanic tribes that had traditionally been enemies (the Cherusci, Marsi, Chatti, Bructeri, Chauci and Sicambri), and was able to set up an ambush in the Teutoburg forest in September of 9 CE. Around 15,000 to 20,000 Roman soldiers died in the battle over three days, effectively destroying the XVII (seventeenth), XVIII (eighteenth), and XIX (nineteenth) legions. Upon hearing of the defeat, the Emperor Augustus was so shaken by the news that he stood butting his head against the walls of his palace, repeatedly shouting “Quintili Vare, legiones redde!” (Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!). But Varus could not hear him. To avoid capture, Publius Quinctilius Varus had committed suicide by falling on his sword.

Author Harry Turtledove has written a novel about the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest called Give Me Back My Legions! (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2009).

Saxons

In the third and fourth centuries CE, new Germanic migrations brought the Saxon people into Westfalen and surrounding regions from their homeland to the north. In their wake came other Germanic tribes—Bavarians, Thuringians, Franks, and Frisian—which joined them in a large confederation.

This confederation became collectively known as the Saxons. For centuries, the area they inhabited was known as Saxony, and eventually as Herzogtum Sachsen (the Duchy of Saxony). The western third of the Duchy was the area that would later be called Westfalen.

The Saxons were originally a small tribe living on the North Sea between the Elbe and Eider Rivers in today’s region of Holstein. Their name was derived from their stone knives called sax.

With the exception of the Saxons, all the other tribal groups were ruled by kings. The Saxons differed in that they were divided into a number of independent tribes under different chiefs, but in time of war they elected a duke to lead them. (The english word ‘duke’ derives from the Latin dux which means leader and was used in Roman times to anyone who commanded troops.)

Karl der Große

Beginning in 772 CE, Karl der Große (Charles the Great), commonly known as Charlemagne (742 – 814), who was king of the Germanic tribe of Franks, came into conflict with the Saxons as both sought to expand their territory. In all, eighteen battles were fought in northwestern Germany during the thirty years of the Saxon Wars, until Charlemagne’s eventual victory.

On Christmas Day, 800 CE, das Heilige Römische Reich (the Holy Roman Empire) was founded with the coronation of Charlemagne by Pope Leo III. After several more uprisings, the Saxons suffered a definitive defeat in 804 CE. The Herzogtum Sachsen (Duchy of Saxony), including the region of Westfalen, now became part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Charlemagne’s new empire was mainly a conglomeration of Germanic lands in Central Europe that lasted for 1,000 years, from 800 to 1806. From the late 15th century onwards, it was also known as das Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation (the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation).

The empire lacked the central authority of a modern state and was actually a union of as many as 300 territories ruled by hereditary nobles, prince-bishops, knightly orders, and free cities. The Kaiser (emperor) was elected by a small group of powerful nobles known as Kurfürsten (elector princes).

Hochstift Minden

In 800, near the end of the Saxon wars, Charlemagne founded the Hochstift Minden (Bishopric of Minden) under the control of the Kirchenprovinz Köln (Ecclesiastical Province of Cologne). As the scattered farms around Hölsen, Hüllhorst and Schnathorst developed into villages, the local people were ruled by the bishops in Minden for over eight centuries until the end of the Thirty Years’ War in 1648.

The larger town of Minden grew out of a second-century Saxon fishing village located at a ford of the Weser river which flows north from there to Bremen and the port of Bremerhaven.

The bishops of Minden reached their highest power under Holy Roman emperor Otto the Great who needed the power of the imperial church to support his rule. Around 950, he provided the bishops of Minden with great estates which eventually covered one-fourth of the territory they controlled. His son Otto II also granted royal prerogatives such as customs, coinage, and market rights in 977.

The bishops were not the only estate holders in the Hochstift Minden. The entire medieval economy was based on the agricultural manor system.

peasants and serfs

The majority of the people in the Middle Ages were peasants. There were generally two classes—serfs and freeholders.

Working the farms of the great medieval estates were serfs—tenant farmers who were bound to a hereditary plot of land and to the will of their landlord. Serfs differed from slaves in that slaves could be bought and sold without reference to land, whereas serfs changed lords only when the land they worked changed hands. Serfs could not leave the manor without permission. If they did not work, they were punished. If the manor land was sold or reassigned to a new owner, the serfs stayed with the land. Serfs had many jobs on the manor including craftsmen, bakers, farmers, and tax collectors.

The majority of the peasants in Hochstift Minden were most likely serfs in the Middle Ages. Freeholders probably represented no more than 10 percent of the peasant population.

Freeholder peasants owned their own land, but usually owed their lord 20 percent of their earnings. They also owed the church 10 percent of their earnings. In return for the fruits of their labor, the lord of the manor would offer protection. In the Middle Ages, war was everywhere. Of course, knights could, and would usually demand additional tributes for keeping these freeholder peasants alive. Overall, the peasant usually retained only 10 to 20 percent of their total work and earnings. Freeholder peasants might own their own business or have room enough for garden of their own. Other than that, their life was just like a serf’s life. A few peasants escaped the hard work on the farm by joining the church. But most lived and died on the manor where they were born.

The only time commoners had a chance to relax and enjoy each other’s company was at a church festival. Festivals offered stage plays, which were religious in nature, along with archery contests, wrestling, dancing, and singing. Often there were jugglers and magicians.

Herzogtum Westfalen

In 1180, Herzogtum Sachsen (the Duchy of Saxony) was divided by emperor Friedrich I (known as ‘Barbarrosa’ for his red beard) and Westfalen became an independent duchy—Herzogtum Westfalen. Friedrich had taken control of the land from a younger cousin, Heinrich der Löwe (Henry the Lion), the Duke of Saxony, who had proved to be overly ambitious and rebellious.

The Duchy of Westfalen was administered for many centuries by its ecclesiastical princes—the bishops of Münster, Osnabrück, Minden, and Paderborn—and especially the archbishops of Cologne.

It was in the early years of the Herzogtum Westfalen that the first written records appeared for Schnathorst (1244), Holsen (1260), and Hüllhorst (1290).

In the later Middle Ages, between the 13th and 17th centuries, many of the most important Westfalen towns—Minden, Münster, Osnabrück, Paderborn, Bielefeld, and Soest—prospered as members of the Die Hanse (the Hanseatic League), an alliance of trading guilds. (Hansa means ‘guild’). The league established and maintained a trade monopoly over the Baltic and North Seas, and most of Northern Europe.

the Black Death

The Black Death was one of the deadliest pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Possibly a form of bubonic plague, medieval people called the catastrophe either the ‘Great Pestilence’ or the ‘Great Plague’. It is estimated to have killed 30 to 60 percent of Europe’s population, reducing the world’s population from an estimated 450 million to between 350 and 375 million in 1400. It took 150 years for Europe’s population to recover.

The widespread devastation created a series of religious, social and economic upheavals which had profound effects on the course of European history. Peasants found new power from the catastrophe. A much smaller workforce found itself in a stronger bargaining position with the lords. Peasants were able to begin freeing themselves from serfdom, and instead began to lease small holdings from the lords. The medieval manorial system began to disintegrate by 1500.

1500s: class and religious warfare

Around 1500, social conditions in the German states were not very good. A newly burgeoning rural population found it difficult to get enough to eat, and many peasants moved to the towns to seek a living. Municipal officials responded by seeking to bar rural newcomers. Within towns that were not prospering, relations between the classes became more tense.

Then, on the eve of All Saints’ Day in 1517, Martin Luther, a professor of theology at Wittenberg University, posted ninety-five theses on the church door there to prompt a debate. The resulting Protestant Reformation soon became marked by violence and extremism, including the Knights’ War (1522-23) and the Peasants’ War (1524-25). The latter rebellion was more serious, involving as many as 300,000 peasants in southwestern and central Germany. (This would have spared Westfalen from most of the ravages.) Although the peasants’ rebellion was the largest uprising in German history, it was quickly suppressed, with about 100,000 casualties.

In 1529, a religious conflict arose in Minden resulting in a band of 36 Protestants taking control of the town government. A year later the town council decreed a ‘Protestant Church Order’ which I assume meant that the bishop no longer had control of the city and that the Protestant church would be legally recognized. However, it wasn’t until the end of the Thirty Years’ War in 1648 that the territory of the Bishopric of Minden was dissolved.

In 1592, the Hüllhorst parish church, which had been been originally founded around 1310 by a priest named Stacius von Tribben, was newly rebuilt for a parish that was now probably Protestant. The existing stone church tower is dated from this sixteenth-century construction.

1618 – 1648: the Thirty Years’ War

Between 1618 and 1648, a devastating European war was fought, principally on the territory of the German states. The Thirty Years’ War involved most of the major European continental powers and was one of the great conflicts of early modern European history and certainly one of the most destructive. The complex war was actually a series of declared and undeclared wars.

In addition, the Thirty Years’ War was also a German civil war. Many of the principalities which made up Germany took up arms for or against the powerful Habsburg rulers or, most commonly, both sides at different times during the war’s 30 long years. It began, however, as a religious war among Catholics, Lutherans, and Calvinists, represented by the religious agendas of the various royal families. Many of Germany’s kingdoms, principalities, and duchies were ravaged by the war.

A major impact of the Thirty Years’ War was the extensive destruction of entire regions, denuded by the foraging armies who were expected to be largely self-funding from loot taken or tribute extorted from the settlements where they operated. This encouraged a form of lawlessness that imposed often severe hardship on inhabitants of the occupied territory.

In this case, the region of Westfalen was directly involved. The church at Hüllhorst was pillaged and damaged in the fighting. In 1634, Swedish troops occupied Minden and remained there until 1650. To make things worse, during this period of widespread warfare, a plague again hit the whole of Germany, decimating the population for five years between 1634 and 1639.

This was a time of terrible suffering in Westfalen and other German states. Episodes of famine and disease significantly decreased the populace of the German states while bankrupting most of the combatant powers. Trade and industry came to a standstill. Towns and cities were in ruins and starving peasants even resorted to cannibalism. Three centuries after the immense suffering of the Black Death, it is estimated that once again half the population of the German states died.

The Thirty Years’ War ended with the Treaty of Westphalia. Actually, there were two peace treaties that ended the war, both signed in Westfalen: the treaty of Osnabrück and the treaty of Münster, signed on May 15 and October 24, 1648.

Fürstentum Minden

The Treaty of Westphalia resulted in replacing the Bishopric of Minden with a secular Fürstentum Minden (Principality of Minden). Its rulers came from the house of Hohenzollern, which originated in Grafschaft Zollern, a countship of the Holy Roman Empire. They held the title of Fürsten or prince-elector of the empire and had a seat at the imperial diet or Reichstag which elected the emperor.

The Hohenzollerns were also dukes of Prussia and over time their dynasty began consolidating its territories into larger units. In 1701, Kürfurst (elector) Friedrich III of Brandenberg intensified that unification when he crowned himself as König (king) Friedrick I of Prussia. In 1719, under the reign of his son, Friedrich Wilhelm I, the Fürstentum Minden was joined with the region to its south, the Grafschaft Ravensberg (County of Ravensberg) to form the Prussian territory of Minden-Ravensberg with the town of Minden as the administrative center. At the time, it was geographically separate from the other Prussian territories.

Friedrich Wilhelm I decreed in 1717 that compulsory public education should be established within his territories for children between the ages of five and twelve, thus affecting the towns of Holsen, Schnathorst and Hüllhorst.

During the period when Prussia had control over these towns, the feudal system was dismantled and tenant farmers of the large estates were given ownership of the land they had farmed for centuries.

1806 – 1815: French and German confederations

During the Napoleonic Wars, on August 6, 1806, Emperor Franz II abdicated the throne of the Heiliges Römisches Reich(Holy Roman Empire), and the 1,000 year empire was dissolved. Napoléon then organized 16 German states into an alliance known as the la Confédération du Rhin (the Confederation of the Rhine), or in German—Rheinbund. During the next six years, 23 more German states joined the confederation. The confederation was above all a military alliance; the members had to supply France with large numbers of military personnel.

Knowing that Prussian armies were poised to invade France, on October 14, 1806, La Grande Armée of Napoléon Bonaparte soundly defeated Prussian forces at the twin battles of Jena and Auerstedt in what is known as the War of the Fourth Coalition. Napoléon marched triumphantly into Berlin.

In 1807, Napoléon seized all Prussian possessions west of the Elbe river. The southern part of this territory was designated as La Royaume de Westphalie (the Kingdom of Westphalia) and was ruled by Napoleon’s brother Jérôme Bonaparte. It was a French vassal state from 1807 to 1813. But this state only shared the name with the historical region of Westfalen, containing only a relatively small part of the territory. La Royaume de Westphalie was a member of the Confédération du Rhin.

Between 1807 and 1810, Minden-Ravensberg which lay to the north of the newly formed kingdom was treated as a de facto part of it known as the Département du Weser (Department of the Weser), Canton de Minden (District of Minden), with Osnabrück as the capital.

However, in 1811 the Canton de Minden (District of Minden) was directly annexed by France and became a part of the French Empire known as the Département de l’Ems-Supérieur (Department of Upper Ems) named after the Ems river. Its capital remained at Osnabrück. The Département de l’Ems-Supérieur was administered on the French model, and was divided into arrondissements and cantons. The French instituted Napoleonic reforms including the end of serfdom, the end of privilege, and the idea of equality under the law. However, Napoléon also demanded large numbers of Westfalen recruits for the French army in preparation for his invasion of Russia.

In 1813, when Napoleon’s campaign in Russia failed, the Confédération du Rhin collapsed as some of its members changed sides against France.

To replace it, the Congress of Vienna (1815) created Deutscher Bund (the German Confederation). During the Congress, the major part of Westfalen was awarded to Prussia and became the Prussian province of Westfalen—Provinz Westfalen of Königreich Prueßen (kingdom of Prussia).

The new province was sub-divided into counties, including Kreis Lübbecke, created in 1815.

1816 – 1819: freeze, famine and disease

1816 was known in Europe and North America as “the year without a summer.” Between 1812 and 1815, there were three major volcanic eruptions around the globe. The Soufriere volcano on St. Vincent Island in the West Indies and Mayon, the most active volcano in the Philippines, both erupted in 1812 creating El Niño weather patterns during the next two years. Then, in April 1815, Mount Tambora, a large volcano on the remote island of Sumbawa in Indonesia, erupted and ejected immense amounts of volcanic dust into the upper atmosphere. This event is believed to be one of the most explosive eruptions of the last 10,000 years. (The infamous Krakatau eruption of 1883 was only one-eighth the size of Tambora.)

The earth was plunged into a volcanic winter. High levels of ash in the atmosphere diminished solar radiation which cooled temperatures worldwide, especially in most high latitude temperate zones. It also led to unusually spectacular sunsets during this period.

On the east coast of the United States, March and April of 1816 were colder and much drier than normal, resulting in an abnormal drought that retarded vegetative growth and withered the grass. Without adequate pasture, livestock had to be fed grain that would normally be used for humans.

In May, severe frosts killed off most of the crops that had been planted. Snow fell across the eastern states in May, June and July. Nearly a foot of snow was observed in Quebec City in early June. In July and August, lake and river ice were observed as far south as Pennsylvania. Although some crops were able to be harvested, grain prices rose dramatically.

Similar effects were felt in Europe. The summer of 1816 is the coldest on record across the continent. Still recuperating from the effects of the Napoleonic Wars, Europe suffered dramatic food shortages and Europeans faced widespread famine. The “year without a summer” soon became known around the world as “the poverty year.”

Grain and bread across Europe prices tripled. Food riots broke out in Britain and France and grain warehouses were looted. The food violence was worst in Switzerland, where famine caused the government to declare a national emergency.

In Germany and Switzerland people were eating cats, rats, and grass. Eyewitnesses wrote of starving people on the Swiss–German border baking ‘bread’ from straw and sawdust. Some Bavarians ate their own horses and watchdogs. In Hungary and parts of northern Switzerland, locals ate rotting cereals and carrion meat.

In addition, huge storms, abnormal rainfall, and flooding of the major rivers of Europe in 1816 have been attributed to the volcanic effects. In Britain, it rained or snowed almost every day that year.

The famine begun in 1816 may also have created conducive conditions for the severe typhus epidemic that impacted southeastern Europe from 1817 to 1819. In 1816 and 1817, nearly 200,000 Europeans died from the combined effects of starvation, typhus and exposure.

1822 – Anton Karl Freidrich Struckmeier

On December 17, 1822, in this time of famine and disease, Anton Karl Freidrich Struckmeier was born at Hof #16 to Georg Heinrich Gottlieb Strukmeier and Anna Marie Elizabeth Cassebaum in the village of Holsen in Kreis Lübbecke, Provinz Westfalen of Königreich Prueßen.

Anton Karl Freidrich was baptized on the day of his birth, December 17, 1822, at the local parish church, the Evangelische Kirche Schnathorst (Evangelical Church of Schnathorst), which served the nearby community of Holsen.

The Evangelical church of Westfalen grew out of a union between Lutheran churches and Reformed churches (which were based on the teachings of the Reformer Calvin). When the Prussian Province of Westfalen was formed in 1815, the Prussian king Frederick William III wanted a unified Protestant church and he issued a “Call to Union” to the two Protestant churches. Part of his motivation was his grief that he had been unable to receive communion with his late wife because she was Lutheran and he was Reformed. In 1817 the Lutheran and Reformed traditions were united into one state church—the Evangelical Church of the Prussian Union. The name Evangelical, which simply means “of the gospel,” was a compromise. In the nineteenth century the term Evangelical indicated a blending of Lutheran and Reformed traditions.

Karl was the second of twelve children. I don’t have a death record of his older sister, Anna Marie Louise Charlotte Struckmeier, so I don’t know if she survived childhood, but the next nine children born after Karl all died within days, weeks or months after their births. Karl’s mother, Anna Marie Elisabeth Cassebaum, died in 1836 at the age of 35 when Karl was just thirteen years old. She died four months after the birth of her twelfth child. Karl may have been the only child in twelve to survive infancy.

His father Georg remarried in November 1836 to Anne Marie Sophie Charlotte Bocker. She brought a son to the marriage, Carl Heinrich Strukmeier, who had been born in January 1836. Carl Heinrich lived to be 56.

Karl spent the first 28 years of his life on the family farm in Holsen and then moved to the nearby village of Hüllhorst from the time of his marriage in 1850 until his emigration to the United States in 1872. Karl’s father, Georg Strukmeier was a farmer and cabinetmaker. As he grew to adulthood in Holsen, Karl learned both skills.

1826 – Anna Katharina Louise Charlotte Greimann

Anna Katharina Louise Charlotte Greimann, was born on November 9, 1826 in house number 27 in the neighboring village of Hüllhorst. She was christened on November 15, 1826 at the evangelical church of Hüllhorst known as Sankt Andreas Kirche (Saint Andrew’s Church) or Andreas-kirche. She was baptized by Heinrich Christoph Wilhelm Koehn, who was pastor of the church from 1820 to 1827.

The Evangelical church in Hüllhorst dates back to around 1310. It was originally a Roman Catholic church until the Reformation. The congregation has a Roman Catholic missal dating to 1510 with inscriptions in it from Peter Thadenhsen, the last priest who served the congregation. He claims to have copied some information from the “old” missal of 1310.

The tower of the church has a stone dating it to 1592, but the brick-faced extension shown in these photos dates from a major renovation in 1871.

Anna’s father Christian Greimann had been born Christian Ludwig Kleine Kottmeier on July 20, 1799. The word Kleine means small in German. The designation Kleine Kottmeier probably distinguised his family from another family who owned a larger farm in the same community, the Große Kottmeiers. On May 14, 1820 Christian Kottmeier married Anne Marie Louise Greimann. Because her family had property, he took her last name in marriage. This was not unusual at the time; the common term was “marrying the farm.” Christian Kottmeier Greimann was also a farmer and cabinetmaker.

When Anna Greimann was born in 1826, the village of Hüllhorst had about 550 people.

daily life in Holsen and Hüllhorst

A sketch of daily life in Hüllhorst was written by Millie Brink Krughoff in 1954 for a family reunion of the Beckmeyer family in Hoyleton, Illinois. Beckmeyer family members lived in houses #10 and #20 in Hüllhorst and some family members emigrated to Hoyleton about the same time as the Karl Struckmeier family in the 1870s. Here are some excerpts:

“In the days when our parents were children in Germany, garments for the whole family were made of linen and wool. Flax was raised on the farm, hand processed, and spun in linen thread. [In] the same way wool was spun into yarn for hose, socks, mittens, shawls, etc., or woven into material for garments. The woolen and linen threads were woven on wooden looms in the home—for men a heavier thread, for women and children a finer thread.”

“After enough cloth was woven, it was taken to a tailor who made garments for the whole family. They were simple and all made after the same pattern. The men wore short trousers, shirts, vests, coats and long, heavy wool hose, which came up over their knees. The women wore linen or wool dresses, all made in the same pattern; plain waist, gathered skirt and [an] apron. Wooden shoes were worn but [by the mid-1800s] people were beginning to wear leather shoes, [sometimes] worn only on Sundays. Shoes were made to order by a cobbler.”

“Furniture was simple and not much of it. A rustic table, wooden chairs, cabinet for cooking utensils and dishes, and a stove in the kitchen, no other stove in the house. A large bed in the bed room and roll away beds for the small children. The small beds were rolled under the large one during the day.”

“Meals were simple and wholesome. For the noon meal, a soup of vegetables and a small piece of meat were cooked during the morning hours and at meal time the soup was emptied into a large bowl, set in the center of the table, where all could help themselves to their share. [They used] wooden spoons, hand-made and polished smooth as glass. Sugar was used very little.”

“Bread baking was done outside in a stone oven. On baking day, a fire was started in the oven and was kept burning until the right temperature for baking, then the coals and fire were removed from the oven and 15 to 20 loaves of bread baked at one time. The bread dough was kneaded in a bake trough (Backtrog). The men did the kneading because it was too much to handle for the women.”

“Cakes, cookies and pastries were baked in bakeries. At a funeral, the upper grade school children had to sing and for this would receive a bun covered with sugar.”

The historical sketch also reported that schooling was provided at a parochial school, operated by the church under the jurisdiction of the state government and referred to as a “state school.”

Hüllhorst became the site of a thriving cigar manufacturing industry starting about 1860. That would suggest that tobacco was raised in the area. When Karl Struckmeyer later emigrated to the United States, he planted tobacco on his Illinois prairie farm.

The Heimatmuseum (the Home or Homeland Museum) in Hüllhorst (shown at the right) was created to showcase rural life and culture in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Located in a remodeled schoolhouse, the museum dates from 1910. It also houses artifacts from a 1999 archaeological excavation in the town. The museum is open on the first Sunday of the month. (See website.)

The current museum director is Dr. Eckard Struckmeier who is also the author of a 1996 history of the Andreaskirche of Hüllhorst. The book is titled “Wie der Hirsch lechzt nach frischem Wasser…”: Geschichte der Kirchengemeinde Hüllhorst vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. In English, it translates as “As the Stag Longs for Clean Water…”: The History of the Parish of Hüllhorst from the Middle Ages to the Present Day. The title is a quote from Psalm 42 which a contemporary English translation renders this way: “As the deer pants for streams of water, so my soul pants for you, O God.” According to information in the book’s outline, Eckhard Struckmeyer served as a Presbyter or Elder of the congregation in 1991.

The parish history was written (unfortunately for me, in German) to celebrate the 125th anniversary of the church’s 1871 reconstruction. Over a three-year period from 1869 to 1871, Karl Struckmeier and his son Ludwig (Louis) participated in the remodeling of the Andreaskirche in Hüllhorst, extending it to its current shape. The book is available through Amazon in Germany (https://www.amazon.de/-/en/Eckhard-Struckmeier/dp/38964690020)

growing up in Germany in the 1830s and 1840s

Karl’s and Anna’s early years may not have been pleasant. In the early nineteenth century, living conditions throughout the German states, and much of the rest of Europe, were not good.

Starting in 1832, when Karl was ten years old and Anna was six, cholera epidemics raged across Europe causing widespread death in Germany, especially in Prussia.

By the 1840s, a huge population growth, combined with harvest failures in 1846 and 1847, meant many people starved. Large numbers of people moved to the cities for work, but working conditions were generally terrible, with long working days and poor or non-existent rights. An economic crisis spread through Europe, sparking food riots and peasant revolts.

A strong liberal democratic movement began forming in Europe to seek such basic rights as freedom of the press, trial by jury, and constitutional systems of government. In Germany, it also included a movement for unification into one nation-state.

At the time, there was no single country called “Germany” or “Deutschland.” There was a German language and a Germanic people, but the ethnic Germans lived in a number of different kingdoms, principalities, and duchies. The collection of 38 German states, including Austria, loosely bound together in the Deutscher Bund (a German Confederation that lasted from 1815 to 1866) were goverened by local rulers with unique laws, taxation, records, and customs duties for transportation of goods.

From 1843 to 1849, Schnathorst was the local center of civil goverment for the surrounding villages. After 1849, that responsibility moved to Hüllhorst.

1848 – the March Revolution

In February 1848, when Karl and Anna were in their twenties, an economic and political uprising in Paris sparked similar armed uprisings in Vienna and Berlin. The various German rulers were frightened enough to grant concessions: they promised liberal constitutions, appointed liberal officials to ministries, promised freedom of the press, the freedom to hold meetings, and the creation of a German national parliament.

In March 1848, a prototype Parliament called for free elections—and the German states agreed. Thus began what became known as the “March Revolution.”

In May 1848, the 550 elected delegates to the first National Assembly met in Frankfurt. They had two primary tasks: to draw up a national constitution and to create a centralized government. They soon formed a temporary Imperial government, but the Assembly was unable to provide this central administration with any real power or authority. The newly created government had no civil service and no army, and a number of the German monarchs refused to swear the allegiance of their troops to the Imperial Administrator. By December, the Assembly had formulated Die Grundrechte des deutschen Volkes (the Basic Rights for the German People) which proclaimed equal opportunity and equal rights for all citizens before the law.

The overriding issue in the creation of a national constitution was setting the borders of the German nation-state. Initially, a majority of deputies favored a “greater German solution” that would include the German-speaking areas of Austria and would separate them from the rest of the Habsburg Empire. Their plans were thwarted when the Austrian Prince introduced a centralized constitution for the entire Austrian Empire.

This marked the beginning of the end for the fledgling German state. The title of Emperor of a Germany without Austria (the “small solution”) was then offered to the Prussian King Frederick William IV. Frederick rejected the offer and spoke out against the 28 German states that had already recognized Austria’s new Imperial constitution.

Turmoil continued into 1849. A large number of liberal delegates left the Assembly, and the republican left became the dominant force. The Assembly was finally forcibly disbanded by the military forces of the Königreich Württemberg (Kingdom of Württemberg).

Disillusioned Germans who believed in free democratic ideals began to emigrate to the United States after 1848, and became known as the “Forty-Eighters.” Many others left for economic reasons, and as military actions were increasing in the unstable political environment, still others sought to avoid compulsary military service.

1850 – marriage

On February 3, 1850, in the midst of this political and social turmoil, Karl Struckmeier married Anna Katharina Louise Charlotte Greimann in the Evangelical Andreas-kirche (St. Andrew’s church) of Hüllhorst. On three consecutive Sundays prior to the wedding (January 6, 13, and 20), marriage banns were announced in church.

Pastor Heinrich August Theodor Gieseler who served as pastor at the church for 52 years from 1832 to 1884, performed the wedding ceremony. The marriage record lists the groom’s name as “Anton Carl Friedrich Strukmeier” and the bride’s as “Anne Catherine Luise Greimann.”

After the wedding, Karl Struckmeier, like his father-in-law Christian Ludwig Kleine Kottmeier before him, moved to the Greimann home at Hüllhorst #27 and helped work the farm. He supplemented his family’s income by carpentry and cabinet making.

1852 – 1866: children

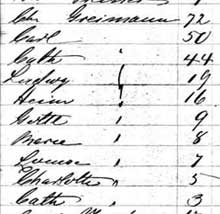

Karl and Anna had nine children, five boys and four girls, all born at #27 Hüllhorst. One son died at childbirth and another died at the age of one.

Karl Struckmeier took the last name of Greimann while he lived in Hüllhorst. Like his father-in-law before him, he too “married the farm.” However, all of the children were baptized as Struckmeier.

- The first, an unnamed male child, died at birth on July 22, 1851

- Ludwig (Louis) Karl Heinrich Struckmeier, was born November 2, 1852

- Heinrich Ludwig Gottlieb Struckmeier, was born February 9, 1855, and died a year later on March 11, 1856

- Carl Heinrich (Henry/Hy) Struckmeier, was born December 20, 1856

- Carl Heinrich Gottlieb (Gottlieb) Struckmeier, was born May 22, 1859

- Anna Marie Sophie Charlotte (Marie) Struckmeier, was born March 23, 1862 (Marie died at age 12 in 1874)

- Anna Marie Catherine Louise (Louisa) Struckmeier, was born March 25, 1864

- Anna Catherine Louise Charlotte (Charlotte) Struckmeier, was born February 21, 1865

- Anna Sophie Marie Charlotte (Anna) Struckmeier, was born March 4, 1866

The last four children, all girls, were born in March or February just one to two years apart. It looks like Anna Greimann Struckmeier conceived again every July, getting only a three-month reprieve between some of these pregnancies.

1862 – 1871: Prussian wars of domination

In 1862, Otto von Bismarck became premier of Königreich Prueßen (the Kingdom of Prussia). Bismarck embarked on a plan to unify Germany under Prussian leadership by means of three deliberately planned wars over the next decade.

In 1864, Prussia and Austria fought Denmark over control of the Duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. In 1866, Bismarck attacked Austria in the Austro-Prussian War, gaining additional territory. The Deutscher Bund (German Confederation) was then dissolved, replaced by the Prussian-dominated Norddeutscher Bund (North German Confederation) which lasted for four years.

Finally, in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), the Norddeutscher Bund (North German Confederation) overwhelmed France. In 1871, Wilhelm I of Prussia was proclaimed Kaiser (emperor) of the Deutsches Reich (German Empire).

At the time the German empire was established, 721 people lived in the town of Hüllhorst.

1869 – 1871: Hüllhorst church renovation

During this period of German nationalism and militarism, Karl Struckmeier and his son, Ludwig, participated in the remodeling of the Andreas-kirche (St. Andrew’s evangelical church) of Hüllhorst over a three-year period from 1869 to 1871, extending it to its current shape.

The original nave was demolished, leaving only the ancient tower remaining. A new three-aisle nave was constructed in neo-Gothic style. In this interior photo, a crucifix dating from 1450 stands at the altar.

Later, this church interior would serve as a model for Die Evangelische Zions Gemeinde (the Evangelical Zion Congregation) in Hoyleton, Illinois.

1872 – emigration

When Karl was 49 years old, he left Hüllhorst and the German Empire behind and took his family to the United States, settling in the fertile prairie of Southern Illinois. The area had been described by previous emigrants as similar in landscape to that of Westfalen (but without the rolling hills and low mountains).

We have no written record of specifically why Karl and his family left Westfalen. However the continuing militarization of the German Empire by Otto van Bismarck may have been one factor. The three boys, Louis (20), Henry (16) and Gottlieb (13) were all potential conscripts for the Kaiser’s armyand his militaristic ambitions. Family lore says that the family left Germany to avoid the draft, and perhaps they did.

According to Millie Brink Krughoff’s historical sketch of the Beckmeyer family in Hüllhorst:

“There was not enough work on the small farm for six boys, and not enough money to send them to college. In those days many young men, yes whole families came to America, where opportunities for business and farming were great. In order to avoid military training, the boys would leave before they were eighteen years.”

Karl Struckmeier’s family received permission to emigrate on August 18, 1872 and left for Bremen on August 29, 1872. Most likely, they traveled to nearby Minden and then boarded a barge on the Weser river which would take them downstream (north) to Bremen.

Joining Karl and Anna and their seven surviving children was Anna’s father, Christian Kottmeier Greimann who was 79 years old. His wife Anne Marie Louise Greimann had died eighteen years earlier in 1854 at age 51.

On September 3, 1872, they sailed for New York on the maiden voyage of the steamship Strassburg, seen at the left. The ship had been launched in May 1872 at the Caird and Company shipyard in Greenock, Scotland for the Norddeutscher Lloyd line. It was one of twenty-two ships operated by that line in 1872.

The Strassburg was 350 feet long with one funnel and two masts, constructed of iron. It had a service speed of 10 knots and could accommodate 60 first-class, 120 second-class, and 900 third-class passengers.

For some time I was unable to find the record of their voyage. I had been searching under the name Struckmeier. When I discovered that Karl had emigrated under his assumed surname Greimann, I was finally able to find the ship’s manifest from the voyage.

Karl’s name is spelled with a ‘C’ and Anna is listed as Catherine, her second given name (Katherina). The ages of the youngest children are incorrect by two to three years and the names of the four daughters are somewhat different from the ones they used in adulthood, but this is clearly the record of their voyage.

The Greimann-Struckmeier family arrived in New York on September 19, 1872. From New York, they may have traveled to southern Illinois by rail. Or, they may have sailed to New Orleans and traveled up the Mississippi by steamboat to St. Louis. Once he settled in Illinois, Karl Greimann again became Karl Struckmeier. The farm he had “married” in Hüllhorst was far behind, and a new life was about to begin.

Hoyleton, Illinois

Karl and Anna Struckmeier and their seven children settled in the small farming town of Hoyleton on the southern Illinois prairie about twelve miles southwest of Centralia in Washington County and 56 miles east of St. Louis. In the late 1800s, Hoyleton’s population was about 300. (In 2005, the population was listed as 550.)

The town of Hoyleton had been founded fourteen years earlier in 1858 by two Congregational ministers and ten families from New York. It was originally called Yankee Town, but was later renamed for Henry Hoyle who was influential in the building of the Hoyleton Seminary in 1860.

Starting about that time, an influx of German settlers soon changed the character of the settlement. One of the leading citizens of the surrounding township was Frederick E. W. Brink (1827-1905), a farmer and co-owner of the Hoyleton mill, who had arrived in the area from Eicksen, Westfalen in September 1844. Letters back home soon persuaded other German immigrants to follow. In 1876, Brink was elected to the Illinois state senate.

1872 – 1879

Karl Struckmeier bought a “quarter section” of prairie north of the town of Hoyleton, built a house, a barn, and other outbuildings, and planted a crop of wheat, potatoes and tobacco. His grandson, Charles Struckmeyer, later recalled that Karl’s and Anna’s home had 16-inch square walnut beams supporting the house.

A “section” of land refers to the practice of surveying a prairie “township” in the form of a square with six miles on each side. The township was then subdivided into 36 square sections like a checkerboard. Each section was a mile square with an area of 640 acres. Thus a quarter section was a half-mile long on each side and contained 160 acres. A modern football field is 1.1 acres, so a 160-acre quarter section was roughly the size of 145 football fields. The sections were numbered starting in the northeast corner, going right to left in the top row (1-6) and then left to right in the second row (7-12), and so on.

A township could ideally support 144 farmers at 160 acres to a farm or 96 farmers at 240 acres per farm. The township was the political and social unit around which life revolved in those days. These 100 or so farmers would elect township boards to determine policies regarding schools and roads.

A 1971 platbook for Hoyleton Township shows a Henry Struckmeyer farm on a quarter of township section 12, just north of and bordering on the town of Hoyleton. This may or may not be the same land farmed by Karl Struckmeyer.

In 1874, two years after they arrived, Karl and Anna’s daughter, Anne Marie Sophie Charlotte (Marie) Struckmeier, died at the age of twelve. A year later, Karl’s father-in-law Christian Greimann died. Both were buried in the Evangelical Cemetery in Hoyleton.

In 1876, Karl’s son, Ludwig (now known as Louis), opened a wagon shop in Hoyleton where he manufactured carriages, buggies and wagons. His father, Karl, and his grandfather, Georg, had both been skilled cabinetmakers and Louis followed in the tradition. He remained a wagon maker for the next 22 years. He also did general carpentry work, and eventually became a building contractor.

The letterhead for his company indicates that sometime between 1876 and 1898, Louis began spelling his last name “Struckmeyer.”

On April 26, 1877, Louis married Henriette Eleanora Detering at Evangelische Zions Gemeinde (Evangelical Zion Congregation) in Hoyleton. She was born in house #5 in the tiny village of Wimmer, Kreis Osnabrück, Königreich Hannover (Kingdom of Hannover) on April 26, 1853. (See Louis Struckmeyer and Henriette Detering)

Henriette arrived in the United States in September 1873 and first settled in St. Louis with her sister Maria Elsabein (Detering) Ahlers. She came to Hoyleton to visit another sister Clara (Detering) Rixman and while there, met Louis Struckmeyer.

Their first child, Anna Catherine, was born on February 21, 1878.

In 1879, Karl and Louis helped with the construction of a new church and school of the Die Evangelische Zions Gemeinde (the Evangelical Zion Congregation) in Hoyleton.

Die Evangelische Zions Gemeinde

The congregation had been founded in August 1861 at the home of Frederick E. W. Brink in North Prairie, Illinois by 18 members of St. Paul German Evangelical Church in Nashville, Illinois. The first church structure was erected in the town of North Prairie in 1862. The day following its completion, a storm leveled the building. It was rebuilt and dedicated in April 1863. The congregation then applied for membership in the Kirchenverein des Westens, the German Evangelical synod for that region.

In 1864, Reverend Philip Karbach (seen at right) accepted a call as the first full-time pastor.

As the congregational membership expanded toward the town of Hoyleton, a controversy arose in the congregation over whether to remain in North Prairie or relocate to Hoyleton. The congregation was seriously divided over the issue.

The majority (nearly three-fourths) of members living in or near Hoyleton finally decide to go their own way and began meeting at the English Congregational church in Hoyleton. They soon began developing plans to construct a new church on a site known as “Hoyleton Hill,” which is the location of the current church.

Construction began in 1867, but could not be completed due to four years of successive crop failures and an economic turndown. For twelve years, piles of wood rotted and bricks deteriorated on the site. The foundation looked like a ruin. In 1870, a schoolhouse was built as the first priority of the community. This also served as a makeshift church. It was in this building that Louis and Henriette were married.

In 1874, a new pastor, Rev. Louis von Rague (seen at left) arrived and was able to reunite the divided factions in North Prairie and Hoyleton. He preached on Sunday mornings and evenings in Hoyleton and on Sunday afternoons in North Prairie. Wednesday night services were held in Hoyleton and Thursday night in North Prairie.

In 1879, a church and school were finally constructed in Hoyleton, using some of the lumber from the church in North Prairie which was demolished. The brick-faced wood frame church was constructed at a cost of $8,000 using volunteer labor. It was modeled after the church in Hüllhorst which Karl Struckmeier had helped remodel a decade earlier.

Karl also crafted a baptismal font which is still in use in the sanctuary today.

The new church was dedicated in February 1880. Today, the church is Zion United Church of Christ, 137 East Saint Louis Street, Hoyleton, IL 62803, 618-493-6317.

1880 – 1889

In the 1880 federal census, Karl was listed as Carl Struckmaear. (The English-speaking census taker, Charles Lively, evidently had problems understanding the German pronunciation of the alphabet). Karl’s wife Anna was listed by her second name Catherin [Anna Katharina Louise Charlotte] perhaps to differentiate her from her youngest daughter who was also named Anna. Henry (22), Gotlibe [Gottlieb] (20), Louisa (16), Charlotte (14), and Anna (11) lived with them. The ages seem a bit off—the oldest, Henry, should have been 23 and the two youngest, Charlotte and Anna, should have been about 15 and 14 respectively on July 8, 1880, the date of the enumeration.

Louis Struckmeier (27), (also misspelled as Struckmaear) lived with his wife Henrietta (Henriette) (26) and his daughter Annie (2). Louis’ occupation was recorded as a wagon maker. A cousin, Charles Struckmeier (also spelled Struckmaear) (17) who was a carpenter, lived in the same household, as did a boarder, Fredric Reis (22), a blacksmith.

Louis Struckmeyer used the blacksmith services of Freidrich Pries in the manufacturing of his buggies and wagons, so perhaps this is another case of misspelling by the enumerator. (The photo at right shows the Fred Pries blacksmith shop in 1910.)

The cousin, Charles Struckmeier, was Carl Heinrich Struckmeier (1863-1898), who was a second-cousin to Louis. Carl was the son of Heinrich Gottlieb Struckmeier and Anna Maria Luise Steinkamp. The common ancestor of these cousins was their great-grandfather Johann Jürgen Struckmeier (1754-1835) who lived in Holsen Hof #16.

Carl Heinrich Struckmeier (the cousin) was born in Holsen in January 1863. He emigrated to the United States in 1880 and so would have arrived just before the census. He later moved to St. Louis and married Bertha Dorothea Koenig. He attended Eden Seminary in Marthasville, Missouri and was ordained in Iowa. He served parishes in St. Louis and San Angelo, Texas. He died in St. Louis from throat cancer at the age of 35 in 1898.

In 1883, Carl Heinrich (Henry or Hy) Struckmeier (son of Karl Struckmeyer and Anna Greimann) married Katherine (surname unknown) at the Evangelische Zions Gemeinde (Evangelical Zion Congregation) in Hoyleton. They had three children born during this decade:

- Louis Struckmeyer, born February 2, 1884

- Minna Struckmeyer, born on Christmas day December 25, 1885

- William Struckmeyer, born February 10, 1889

On February 14, 1884, Anne Marie Catherine Louise (Louise) Struckmeier married Christian Heinrich Friedrich (Christ) Koelling, a farmer, at the Evangelische Zions Gemeinde (Evangelical Zion Congregation) in Hoyleton. Christ Koelling had been born in house #3 in the village of Holsen, Westfalen in 1858. He emigrated to Hoyleton in 1882. They had eleven children over the next 22 years in Hoyleton:

- Carl Frederich Louis Koelling, born November 23, 1884. He died in 1889 at age 5.

- Anna Catherine Henriette Koelling, born November 17, 1886

- Martha Charlotte Marie Koelling, born December 16, 1888

- Heinrich Gottlieb Frederich David Koelling, born June 30, 1891. He died in 1892 at age 8 months.

- Alma Louise Anna Koelling, born August 23, 1893

- Albert Frederich Wilhelm Koelling, born February 8, 1896

- Louis Carl Frederich Koelling, born March 3, 1898

- Yohannah Elizabeth Alwina Koelling, born March 5, 1899

- Paul Louis Heinrich Koelling, born December 6, 1901

- Heinrich (Harry) Carl Louis Koelling, born February 21, 1905

- Frances Minnie Clara Bertha Koelling, born June 25, 1906

In 1887, Carl Heinrich Gottlieb (Gottlieb) Struckmeier married Martha Marie Wiese at the Evangelische Zions Gemeinde (Evangelical Zion Congregation) in Hoyleton. They had six children born over the next thirteen years:

- Carl Heinrich Struckmeyer Sr., born October 30, 1888

- Bertha Struckmeyer, born in 1891

- Martin Heinrich Struckmeyer, born October 3, 1893

- Hannah Henriette Marie Struckmeier, born February 16, 1896

- Paul Heinrich Struckmeyer, born August 7, 1898

- Otto Struckmeyer, born April 12, 1900

On February 24, 1887, Anne Sophie Marie Charlotte (Anna or Charlotte) Struckmeier married Friedrich (Fritz) Niemeier, a blacksmith, in the nearby town of Irvington, Washington, Illinois. (In the 1920 census, Charlotte was listed as Schlotta). Charlotte and Fritz had four children—all boys—born in Irvington, Illinois over the next ten years:

- Louis Carl Niemeier, born May 20, 1888

- Frederick H. Niemeier, born March 1, 1890

- Arthur Fredrick Niemeier, born July 9, 1893

- Carl Frederick Niemeier, born April 25, 1897

In October 1887, Die Evangelische Zions Gemeinde (Evangelical Zion Congregation) in Hoyleton celebrated their 25th anniversary. The church had 96 families and 90 children attended the parochial school.

On October 24, 1889, Anna Catherine Louise Charlotte (Charlotte or Anna) Struckmeier married the Reverend Karl (Carl) Friedrich Ferdinand Schnake. Karl was born in Hof #73 in Tengern, Westfalen in 1860. He received his preliminary theological education at the Bruderhaus Nazareth in Bielefeld, Germany and in 1884 ran a Christian hospital for epilectics in the city of Harlem in the Netherlands. He emigrated to the United States in 1886 and finished his theological education at Eden Seminary in Wellston, Missouri, located just outside of the city of St. Louis. Catherine and Karl had eight children born in Missouri and Illinois over the next 21 years:

- Paul Carl Schnake, born August 16, 1890

- Hedwig Schnake, born in September 1892

- Hulda Marie Schnake, born June 14, 1894

- Armin Carl Otto Schnake, born April 2, 1896

- Olga Charlotte Schnake, born August 9, 1897. She died on November 17, 1897 at age 3 months.

- Emil Christ Schnake, born in February 1899. (He was listed in the 1900 census as Emily!)

- Alfred Schnake, born in 1901

- Reinhardt Schnake, born in 1910

(For more detailed information, see Karl Schnake and Anna Struckmeier)

1890 – 1899

No census record is available for 1890. [Note: The Federal Census of 1890 was destroyed by a fire at the Commerce Department in Washington, D.C. on January 10, 1921. The surviving fragments of 1,233 pages list only 6,160 of the 62 million people counted.]

This photo (at left) of Anna and Karl Struckmeier was taken at the Evans photographic studio in Centralia, Illinois, date unknown. It is the only photo of either that is known to exist.

Anna Greimann Struckmeier died on March 19, 1897 at the age of 70. She was buried in the Zion Evangelical Cemetery in Hoyleton.

1900 – 1901

By the time of the census of 1900, the 77-year-old Karl was widowed and was living at the farm with his son Gottlieb (41), Gottlieb’s wife and six children. Mary Greimann, age 17, a servant, lived with the family. Gottlieb now managed the farm and eventually owned the property.

Carl Henry Struckmeyer and the Hoyleton Orphan’s Home

One of Gottlieb Struckmeier’s children was Carl Christian Heinrich (Carl Henry) Struckmeyer, who became a very well-respected educator and school administrator, and was a leading citizen in the town of Hoyleton.

Born on October 30, 1888, Carl trained as a teacher at Elmhurst College in Elmhurst, Illinois. He later received a Masters Degree at Washington University in St. Louis. For 29 years, he lived in Monroe County, Illinois, where he began his career as a parochial school teacher in the town of Waterloo. The 1920 Census lists him as the principal of Maeystown High School, and by the census of 1930, he was Superintendent of Schools at Columbia, Illinois. Carl was also a fine musician. He served as a church organist for 50 years, twenty-five of those at Zion Evangelical Church in Hoyleton, where he also directed the church choir.

In November 1913, Carl married Ida Marie Busse (1886-1976). They had three children:

- Carl Heinrich Struckmeyer, born June 21, 1915

- Glen Martin Struckmeyer, born February 27, 1918

- Ruth Struckmeyer, born July 4, 1925

Carl and his wife Ida eventually ran the Hoyleton Orphanage Home (later the Hoyleton Children’s Home and today known as Hoyleton Child and Family Services), where he served as director from 1939 until his retirement in 1952 at age 64. Carl died in Hoyleton in September 1964 at age 75.

The Hoyleton orphanage had been created through the efforts of Rev. Frederick Pfeiffer, the pastor of Zion church from 1881 to 1896. Pastor Pfeiffer was reportedly a warm-hearted man who had a special concern for orphans. When local children were orphaned, he would take them into his home until he could find foster and adoptive parents within the congregation. In 1894, he organized the Orphan Association in the South Illinois District of the German Evangelical Synod of North America with congregations in nearby towns.

The association was then given title to a vacant seminary building which had been built during the time when Hoyleton was a largely English-speaking settlement. The Hoyleton Seminary was a stately white frame building constructed in 1860 by members of the the Hoyleton Congregational Church with assistance of the Central Railroad Company. At the time, Hoyleton had only been settled for two years. From 1884 to 1894, it was used as a public school building. Then the building and an endowment fund was given by the dwindling English-speaking Congregational Church to the growing German-speaking Zion Evangelical Church to be used for charitable purposes.

A member of Zion Evangelical Church, Mr. and Mrs. Louis Beckmeyer, became the first orphan parents of the home. The building was expanded in 1903, but burned to the ground in June 1915. A new brick building was then constructed which serves today as the headquarters for Hoyleton Child and Family Services of the United Church of Christ (UCC).

From Struckmeier to Struckmeyer

At some point, perhaps around 1900, the spelling of the family name was gradually being changed from Struckmeier to Struckmeyer. The family lore is that there was some disagreement with another local family named Struckmeier and the name change was made to differentiate the two. However the change appears to be gradual, family by family, and somewhat inconsistent. In 1901, Karl’s name was spelled Struckmeyer in his obituary and Struckmeier on his grave marker.

On October 27, 1901, at age 78, Karl Struckmeyer, who suffered from asthma, fell asleep in his rocking chair and never awoke. He was buried three days later in the Zion Evangelical Cemetery in Hoyleton.

The following is an English translation of a German obituary that appeared in a local paper:

Mr. K. Struckmeyer, an eminently respected citizen of Hoyleton, Illinois, went to sleep Sunday night into a better world beyond. The deceased was born on December 17, 1822, in Holsen, Schnathorst, Westphalia, and moved to this country in 1872, settling near Hoyleton.

In 1850 he was joined in marriage with Anna L. Greimann, who preceded him into eternity four years earlier.

The deceased was an energetic member of the Evangelical Church in Hoyleton, a model to all for his faithful service, and whose memory will always be honored.

By profession he was a skilled cabinetmaker, and he finished the interior of the church in Hüllhorst [Westphalia]. That church served as the model for Zion Church in Hoyleton, where he also artfully crafted the baptismal font.

The deceased had long been suffering with asthma, but on some days he was still walking around the farm. As evening approached, he had difficulty breathing, but he did not want to go bed, instead staying in his rocking chair, where he later fell asleep.

He would never again awake on earth—his slumber became the sleep of death. Death came painlessly at 3 AM. The funeral was held on October 30, [1901] at Zion Evangelical Church in Hoyleton. Rev. Schroedel [seen at right] preached a homily rich in comfort on Psalm 31:6, a text chosen by the deceased.

His journey home is mourned by six children: Louis Struckmeyer of St. Louis, Hy and Gottlieb Struckmeyer and Louise Koelling of Hoyleton, Charlotte Niemeier of Irvington and Mrs. Pastor Anna Schnake of Drain, Missouri. The burial followed at the Evangelical Cemetery.

Psalm 31:6 reads “I hate those who cling to worthless idols: I trust in the Lord.”

Karl and Anna’s children

Ludwig Karl Heinrich (Louis) Struckmeier died on December 14, 1905 in St. Louis, Missouri.

Carl Heinrich (Henry or Hy) Struckmeier died on June 30, 1921 in Hoyleton.

Anna Catherine Louise Charlotte (Anna) [Struckmeier] Schnake died on July 13, 1930 in Hoyleton.

Anna Marie Catherine Louise (Louise) [Struckmeier] Koelling died on June 19, 1931 in Hoyleton.

Carl Heinrich Gottlieb (Gottlieb) Struckmeier died on August 4, 1939 in Hoyleton.

Anna Sophie Marie Charlotte (Charlotte) [Struckmeier] Niemeier died on January 8, 1950 in Irvington, Illinois.