1844 – Michel Schüller

Michel (Michael) Schüller was born on September 30, 1845 to Alphonze Schüller and Sophia Tomas in the village of Bergheim, Alsace, a region of La Royaume de France (the Kingdom of France). At that time, the territory was ruled by the French monarch Louis-Philippe d’Orléans. The only clue we have to Michel’s hometown was a French Citizenship Declaration in 1872 when he was 27 years old.

The family was Roman Catholic, as Alsace was a heavily Roman Catholic region. They spoke German.

Today Bergheim is a village in the Ribeauvillé-Riquewihr region of Alsace’s wine country. It lies along the Alsace Wine Route about 4 km (2.5 miles) northwest of the village of Ribeauvillé. It is located about 18 km (11 miles) north of the city of Colmar.

The origins of Bergheim remain uncertain but the discovery of a Roman mosaic attests to the presence of villas in the time of the Roman Empire.

Bergheim is one of the rare Alsace towns to have almost completely preserved its medieval town walls (built in 1311). It is a completely fortified town and has an ancient and remarkable church, as well as magnificent towers and walls. The village has not had a peaceful past, and is said to have changed hands more often than anywhere else in Alsace, especially in the turbulent period between 900 and 1300. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Bergheim was the scene of many witch trials, that sent 40 women to the stake. The entire population was wiped out by two wars and the plague in the 17th to 18th centuries. To replace the population, thousands of people from other countries were invited to immigrate to Bergheim. The majority of people who immigrated at that time were Swiss, German, Hungarian, Austrian, or Romanian.

confusing records

Sorting out genealogical facts can be very confusing. According to the 1910 census, Michel Schüller was born in Germany and spoke German. But according to the 1920 census, he was born in Alsace-Lorraine and spoke French. By 1930, the census records become a bit more accurate—Michael was born in Alsace-Lorraine (partially correct) and spoke German. At the time of his birth, Alsace was a part of France, but large parts of the population were of Germanic origin and spoke German.

Mühlhausen

Apparently, sometime after 1881, Michel Schuller moved to the much larger town of Mühlhausen. When Michael Schuller’s son, Michael, registered for the U.S. draft in 1917, he listed his birth place as “Muelhausen, Elsace, France.”

The name of the town was actually Mühlhausen (German for mill houses). In the Alsatian Swiss-German dialect, it was known as Milhüsa. Today it is a large sprawling industrial city known as Mulhouse (pronounced my-luz in French). It is the second largest city in Alsace after Strasbourg.

Mulhouse is the largest city in the southern part of Alsace known as the département du Haut-Rhin (Department of Upper Rhine) The northern half of Alsace is the département du Bas-Rhin (Lower Rhine). The upper and lower designations refer to the relative elevation above sea level. The southern half is near the Swiss Alps, hence the upper designation.

The first written records of Mühlhausen date from the twelfth century when it attained status as a free town. In 1354 Mühlhausen became part of an alliance of ten Imperial cities of the Holy Roman Empire in the Alsace region called the Zehnstädtebund (Décapole in French and Decapolis in English). In 1515, Mühlhausen pulled out of the alliance in order to ally with the Swiss cantons as an independent republic. Mühlhausen is located just 20 miles northwest of Basel, Switzerland. It was closely allied with the canton of Basel and was considered a Swiss town for over 250 years of its history.

In 1648, at the end of the Thirty Years War, the Holy Roman Empire was disbanded and much of Alsace was ceded to France by the Treaty of Westphalia. However, Mühlhausen remained a Swiss town until 1798 when, at the peak of its prosperity (based on the manufacture of printed cotton fabrics), it voted to become a part of France also. This was a purely pragmatic decision. At the time, a French blockade of the Swiss cantons forced the city leaders to ask France for unification in order to continue to trade and prosper.

Fifty years earlier, in 1746, four young men from Mühlhausen founded the city’s first textile printing works where they developed dyeing and printing techniques for calico cotton fabrics. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the city of Mühlhausen grew rapidly, largely due to the implantation of numerous textile printers. In 1789, Mühlhausen had 6,600 inhabitants. By 1851, the population had grown to 29,500. In the 19th century, Mühlhausen and the surrounding Alsace area became world leaders in the manufacture and marketing of chintz and other printed cloth.

Alsace

Alsace is an eastern region of France that is separated from Germany by the Rhine river. Alsace is oriented along a north-south axis on a fertile plain tucked between the Rhine River on the east and the forests of the Vosges (pronounced vōzh) mountains on the west. It is about four times as long as it is wide.

The agriculturally rich lower area is checkered with vineyards, while the higher slopes are forested and sprinkled with monasteries and old castles. To the west lies the Lorraine region of France, to the south is Switzerland, and to the east across the Rhine is the Schwarzwald (Black Forest) of Germany.

Alsace was part of the Holy Roman Empire and its successors from 841 to the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. For eight centuries it was ruled by Germanic leaders including the Hohenstaufen Emperors in the 12th and 13th centuries and the Habsburgs (often Anglicised as Hapsburg) in the 14th to 17th centuries. In 1648, Alsace became a French territory for the first time.

After the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1871, Alsace was ceded to Germany, along with the region of Lorraine, and became the Reichsland Elsaß-Lothringen (the Imperial Country of Alsace-Lorraine). The combined region remained under German control for nearly 50 years until the end of World War I when the territory was returned to France in 1919 and once again became separated French regions. (Alsace was destined to become German territory again in 1940 before being reunited with France once more in 1945.)

Therefore, before 1871 anyone from Alsace would have been considered French. From 1871 to 1918 they would have been considered German. After 1918, they would have once again been considered French. So in the 1900 and 1910 U.S. census records anyone from Alsace would generally be listed as having come from Germany. In 1920 and 1930, Alsatians would generally be listed as having come from France.

The Vosges mountains to the west of Alsace provided a natural barrier to French language and culture during much of Alsace’s history. The Alsatians developed a unique Swiss-German dialect and a Germanic culture and architecture. After the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, the French government began to teach French in Alsatian schools, but the common people retained their own dialect for day to day activities. After the Franco-Prussian war, it was once again German language and culture that was taught and French influences were suppressed.

The Schullers from Alsace reflect this back and forth history. They descended from Germanic roots and they spoke German. (Schüller is a derivative of schüler, German for student, pupil, or scholar). Yet the Schullers considered themselves French as did most Alsatians. The people of Alsace were French in spirit, proud to belong to the country generally regarded as the most civilized in Europe at the time, yet they always retained their historic Germanic customs and dialects.

1855 – Salomea (Salomé) Thomas

Salomea (Salomé) Thomas, was born in Alsace in April 1855 during the reign of French Emperor Napoleon III. According to the 1920 census, both her parents were born in Alsace also. We have no record of their names.

According to her death record, Salomé’s maiden name was Thomas, which I considered to be an unusual name for an Alsatian, because it looks like an English spelling—not French or German. But birth records of her younger sons in Alsace confirm that Thomas is the correct spelling. They also list her given name as Salomea.

trivia: Alfred Dreyfus and Albert Schweitzer

This is just an interesting aside, but Michael and Salomé were contemporaries with Alfred Dryfus, a French military officer best known for being the focus of the “Dreyfus Affair.” Dreyfus was born in Mühlhausen to Jewish parents on October 9, 1859. He was framed for an act of espionage and arrested for treason on October 15, 1894. In January 1895, he was sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island. Dreyfus won a retrial after Émile Zola published a front-page letter to the French President, entitled J’Accuse! He was eventually exonerated in 1906.

Another bit of trivia is that Albert Schweitzer was born in the nearby village of Kaysersberg, Alsace on January 14, 1875. The son of a Lutheran pastor, Albert attended high school in Mühlhausen. He was 20 years younger than Michael and Salome, but was just two years older than their first child Alphonse Joseph Schuller, who was born on March 5, 1877. The Schullers emigrated to the United States in 1888 when Alphonse was just 11 years old, so he and Albert Schweitzer would not have been high school classmates.

1860 – 1869

Michael Schuller became a carriage maker and a blacksmith. Perhaps his father Alphonze had those trades also. Michael later taught his eldest son Alphonse the skills of the blacksmith/farrier trade.

1870 – 1879

In 1870, when Michael Schuller was 26 and Salomé was 16, Prussia went to went to war with France. Michael either enlisted or was drafted into the army of Emperor Napoléon III where he served as a fencing master. The portrait at the left of Michael in his military uniform is in the posession of a decendant of his daughter, Minnie Schuller.

Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte was the nephew and heir of Napoléon Bonaparte. He was elected as the first president of La Deuxième République (the Second French Republic) in 1848, but in 1851 he he initiated a coup d’état and was crowned emperor Napoléon III of Le Second Empire Français (the Second French Empire). In 1870, the emperor mobilized the Armée de Châlons and declared war on Prussia. But the other German states of the North German Confederation quickly joined on Prussia’s side. The Franco-Prussian war was largely fought in Alsace and resulted in terrible destruction and loss of life. A series of swift Prussian and German victories in eastern France culminated in the Battle of Sedan on September 1, 1870, at which Napoléon III and his whole army was captured the following day. After the fall of the emperor, La Troisième République (the Third French Republic) was formed and continued to wage war with the Prussians.

A newspaper article about Michael and Salome Schuller’s 60th wedding anniversary indicated that Michael also fought in a revolution following the reign of Napoleon III. I have no information about a revolution, but perhaps it refers to the war waged after the capture of the emperor. If so, Michael was not captured at the Battle of Sedan, but continued to serve in the army of the Third Republic.

One of the outcomes of the war was the unification of Germany and proclamation of Prussian King Wilhelm I as Deutscher Kaiser (German Emperor) on January 18, 1871. He was crowned in the Hall of Mirrors in the Versailles Palace outside of Paris.

At the war’s conclusion in 1871, Alsace was ceded to the new German Empire or Deutsches Reich. Along with the region of Lorraine, Alsace became part of the Reichsland Elsaß-Lothringen (the Imperial Country of Alsace-Lorraine), a territory of the German Empire ruled by Emperor Wilhelm I and his prime minister Otto von Bismarck. The transfer caused an estimated 50,000 people (about 3 percent of a total population of about a million and a half) to emigrate from the region westward to France and to America.

A policy of Germanization banned the French language in schools and all newspapers had to be printed in German. There was tremendous anger and resistance in Alsace over German domination. Even though the Schuller family was culturally German, they considered themselves to be citizens of France and claimed that nationality.

The Alsatian sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi (1834-1904), in exile in Paris, created his famous Statue of Liberty for the U.S. Centennial of 1876, saying that it represented for him precisely that freedom which he and his fellow Alsatian were being denied.

marriage and children

In 1873, Michael Schuller and Salomé Thomas were married in a Roman Catholic parish in Mühlhausen, in the new Reichsland Elsaß-Lothringen. Salome was 19 and Michael was 29.

Based on the 1910 U.S. census records we know that over the course of their marriage Salomé gave birth to 11 children. Five died in infancy or childhood, most likely in Alsace. Only six survived to adulthood. Of the five children who died, we only have the name of one—Elizabeth—whose birth date is unknown.

Their surviving children included four sons who were born in Alsace. The first was born in the 1877.

- Alphonse Joseph (Alfie) Schuller, born March 5, 1877 in Alsace

There is some reason to believe that their first son, Alphonse Joseph Schuller, may not have been born in the town of Mühlhausen. His grave marker states that he was born in Paris. Although possible, this birth place is not likely. Other documents indicate his birthplace as Alsace.

Alphonse, who had quite a sense of humor, sometimes claimed that he was born in a town named “Infillibippi.” I have not been able to find any town in France with a name resembling that and, from experience, I would take his claims with a grain of salt. Alfie also told his grand-daughters that he was descended from King Alphonse of Spain and that therefore they were royalty—princesses. “But,” he cautioned them, “don’t tell the other children.”

1880 – 1889

The next three children, all sons, were born in the decade of the 1880s.

- Joseph A. (Joe) Schuller, born March 17, 1881 in Alsace

- Anton (Tony) Schuller, born on May 14, 1885 in Mühlhausen

- Michael (Mike) Schuller, born November 26, 1886 in Mühlhausen

1888 – emigration

In April 1888, the family left Alsace and emigrated to Saint Louis, Missouri in the United States. There is no record of what caused the decision to emigrate.

On April 16, 1888 the ship La Bourgogne arrived in New York from Le Havre, France. The ship’s manifest includes Michel Schuler (43), Salomé (31), Alphonse (11), Joseph (7), and Antoine (4). Note the French spellings of Michael (Michel) and Anton (Antoine). Their youngest son Michael is not listed on the manifest. He would have been about 16-17 months old at the time of the voyage.

Built in 1885 for the Compagnie Generale Transatlantique, La Bourgogne was constructed of iron and steel with two funnels and four masts. She was a 7,395 gross ton vessel, with a length of 494.4 feet and a beam of 52.2 feet. She was propelled by a single screw and had a speed of 17.5 knots. La Bourgogne could carry 1,055 passengers—390 in first class, 65 in second class, and 600 in third class.

She sailed on her maiden voyage from Le Havre to New York on June 19, 1886. That year she raced against time and crossed the Atlantic in seven days, winning first place in the New York postal service competition.

La Bourgogne is famous because of a disaster which occurred 10 years after the Schuller’s voyage. On July 4, 1898, on a voyage from New York to Le Havre, La Bourgogne was sunk in a collision with a British coal ship, the Cromartyshire, in a deep fog off Newfoundland. La Bourgogne had 726 persons on board—506 passengers and 220 crew members. 549 people drowned.

1890 – 1899

After the family’s arrival in the United States, census records help to fill in some of the gaps in the family’s story. Unfortunately, no census record is available for 1890. The Federal Census of 1890 was destroyed by a fire at the Commerce Department in Washington, D.C. on January 10, 1921. The surviving fragments of 1,233 pages list only 6,160 of the 62 million people counted.

When the Schullers arrived in St. Louis in 1888, the population was about 145,000, with 1,717 residents who were born in France and 66,000 born in Germany. We don’t know where they first settled, but by 1900 the Schuller family was living the Soulard area of St. Louis, just south of downtown.

Soulard is one of the oldest neighborhoods in St. Louis with homes dating from the mid to late 1800s. The area was named for a French surveyor, Antoine Soulard, who surveyed the area for the King of Spain while St. Louis was under Spanish control from 1763 to 1800. During that period, St. Louis was a part of the “Ylinneses” region of the province of “Luisiana.” The Soulard community was annexed by the city of St. Louis in 1841.

There is a record in the 1890 St. Louis City Directory of a Michael Schuller living at 1003 Allen Avenue, between 10th Street and Menard Street, in the Soulard neighborhood. He is listed as a laborer.

Just three blocks east in the Soulard neighborhood is Saints Peter and Paul Church, a Roman Catholic congregation founded in 1849 to minister to German immigrants. Located at 1919 Seventh Street at Allen Avenue, the current German Gothic structure was constructed in 1875. The church, with a steeple more than 214 feet high, was built to seat 1,500 people.

We can assume that the Schullers were members of this church because their children were baptized there and Michael, Salome and Anton are buried in the Sts. Peter and Paul Cemetery in South St. Louis. (The entrance to the cemetery is located at 7030 Gravois Avenue and their graves can be found on a hill just south of Loughborough Avenue.)

A parochial school was conducted in a large story building adjoining the church on Eighth Street.

Over the next several years, Michael and Salomé’s two surviving daughters were born:

- Minnie L. Schuller, born January 2, 1889

- Marie (Mary) Salome Schuller, born June 21, 1891

After seven years in the United States, the six Alsace-born members of the Schuller family became naturalized citizens in 1895.

In 1895, Gould’s St. Louis City Directory listed Michael Schuller as a blacksmith living at the rear of 1003 Allen Avenue.

On May 27, 1896, a powerful tornado struck St. Louis, destroying or damaging over 8,800 buildings, killing at least 138 people, and injuring over 1,000 more. The twister touched down in the southwestern portion of the city and moved northeast in a zigzag course more than two miles long and a mile wide. In its course, the tornado severely damaged Saints Peter and Paul Church and many buildings in the Soulard area, including the City Market. The tornado crossed the Mississippi river at Eads Bridge and caused additional destruction in the city of East St. Louis. It was one of the most devastating disasters in St. Louis history.

In 1899, Gould’s St. Louis City Directory listed Michael “Schuler” as a blacksmith residing at 1724 South Broadway, with Alphonse “Schuler” as a “shoer” at the same address.

1900 – 1909

In the 1900 census we learn that Michael Schuller (55) and Salomé (45) were living with their six children at 316 Lafayette Avenue, between South 3rd Street and South Broadway, in St. Louis. Their home lay just two blocks from the railroad tracks that ran along the banks of the Mississippi. Michael’s occupation was a blacksmith. Sons Alfonso (23), Joseph (20), Anton (15) and Mike (13) were working as a blacksmith, a laborer, a clerk and a machinist’s assistant respectively. Minnie (11) and Mary (9) were in school.

Alphonse Schuller soon left the household. He married Emma Bauer on July 18, 1901 in St. Louis, Missouri, most likely at Sts. Peter and Paul church. He was 24 and she was 20. (See Alphonse Schuller and Emma Bauer) Emma was the daughter of Gustav Bauer and Christine Bauer. She was born May 19, 1881 in St. Louis, Missouri.

Alphonse and Emma Schuller had four children all during this decade:

- Alice Elizabeth Schuller, born October 7, 1901

- Alphonse Joseph Schuller Jr, born July 20, 1902, died November 23, 1902

- Elmer John Schuller, born September 8, 1903

- Kenneth Gustave Schuller, born September 27, 1909

Sometime between 1900 and 1903, Joseph Schuller married Margaret (surname unknown). She was born in 1881 in Illinois to unrecorded parents. They had one child:

- Mildred Schuller, born in 1904

From April 30, 1904 to December 1, 1904. the Louisiana Purchase Exposition was held in St. Louis, celebrating the centennial of Thomas Jefferson’s major addition to the territory of the United States. The World’s Fair was located on the present-day grounds of Forest Park and Washington University, and was the largest fair to date with over 1,500 buildings. Exhibits were staged by 62 foreign nations, the United States government, and 43 of the 45 U.S. states. The Fair also hosted the 1904 Summer Olympic Games, the first Olympics held in the United States. These games had originally been awarded to Chicago, but when St. Louis threatened to hold a rival international competition, the games were relocated.

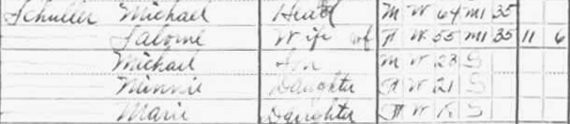

1910 – 1919

In 1910, Michael (64), Salomé (55), and their children Michael (23), Minnie (21) and Marie (19) were living at 815 Geyer Avenue, between 8th and 9th Streets, about 4 blocks west of their previous address on Lafayette. Michael senior was a blacksmith for a boiler maker. The John Nooter Boiler Works Company was located nearby in the Soulard area. They began manufacturing pressure vessels in the 1890’s. Perhaps Michael worked there. Young Michael was a foreman at a buggy works, Minnie was a stitcher at a shoe factory, and Marie was a stenographer in an office. After 12 years in the United States, the census says that Michael and Salome still spoke German, not English.

In 1910, Alphonse Schuller (33) was living at 4609 Easton Avenue, about six blocks east of Kingshighway Boulevard in north St. Louis, with Emma (28) and their three children: Alice (8), Elmer (6) and Kenneth (7 months). Alphonse was a horseshoer or farrier who owned his own blacksmith shop. (Today, Easton Avenue has been renamed Dr. Martin Luther King Drive.)

Within the next seven years, Alphonse opened his own company, the Schuller Auto Repair Company at 4543 Delmar Avenue. Horses were a thing of the past, and for someone skilled at working with metal, Alphonse decided auto repair was the future.

In 1910, I found no census record for either Joseph Schuller or Anton Schuller.

In 1914, Marie Schuller married George Hugh Roninger. He was born January 24, 1890 in Columbiana, Ohio where he was christened as George Hugo Ronninger.

George and Marie (Mary) Roninger had four children, the first two born in this decade:

- Louis Elmer Roninger, born April 13, 1915, in St. Louis

- Robert H. Roninger, born in 1917 in St. Louis

In June 1917, George Roninger (27) registered for the draft. He was living at 3909A Wyoming in St. Louis with his wife Marie and his two sons Louis and Robert. He was a manager of sales promotion for the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company. He had 3 years of military service in the artillery.

In 1917 and 1918, the four Schuller brothers also registered for the draft.

In June 1917, Michael Schuler (30) registered. He was living at 908 Russell Avenue. He listed his employment as hat maker and his employer as the Norris Polk Hat Company at 1227 Washington Avenue in St. Louis.

In September 1918, Alphonse Schuller (41) registered. His address was 1343 Walton, between Page and Easton, in St. Louis. He listed his occupation as auto repair work at Schuller Auto Repair Company, 4543 Delmar Avenue, about eight blocks south of his home.

In September 1918, Joseph Schuller (37) also registered. He was living at 1005 Lafayette Avenue in the Soulard area. His registration card listed his occupation as a motion picture operator at the Majestic Theater at 11th Street and Franklin Avenue. His wife’s name was spelled “Margariette.”

In September 1918, Anton Schuller (36) also was registered for the draft. At the time, he was an inmate at the City Sanitarium at 5400 Arsenal Street in St. Louis. He was found unfit to serve in the military because he was declared “insane.”

Opened in 1869 as the St. Louis County Insane Asylum, the hospital was renamed the St. Louis Insane Asylum after the City of St. Louis separated from the County of St. Louis on October 22, 1876. Located on elevated ground on Arsenal Street, west of Kingshighway (about 4 miles southwest of downtown St. Louis), the hospital consisted of a 5-story central building, flanked on each side by 4-story wings with 5-story end pavilions. The 194-foot cast iron dome on the central building was visible across much of the city. It was renamed the City Sanitarium in 1910 and extensive additional wings were added in 1912.

Sometime around late 1917 or early 1918, Minnie Schuller married Edward Seemiller. He had been born on November 6, 1892 in St. Louis, Missouri. He must have had a difficult childhood. His mother was dead by the time he was seven and his father, Frederick Seemiller, gave his care over to Edward’s aunt and step-uncle, Adam and Katherine Krahling. By the time he was 17, as indicated by the 1910 census, Edward was living with his grandmother, Louisa Finley, and a cousin, Viola Gunther, who was also under her grandmother’s care. In 1910, Edward’s father, Frederick (76), was an inmate at a city infirmary (which the census notes was formerly the St. Louis Poor House). Three years later he was dead of colon cancer and peritonitis at age 79. Edward was an orphan by the time he was 20 years old.

The 1910 census revealed that both Edward Seemiller and Minnie Schuller were employed at shoe factories. Whether they worked together is difficult to determine. There were 32 shoe factories in St. Louis in 1910. The Brown Shoe Company had constructed a factory at 1201 Russell Boulevard in 1904. It was known as the “Homes-Take Factory.” The building still exists. In 1917, when Edward registered for the draft, he indentified his occupation as a shoe worker at Peters Shoe Company located at 12th Street and N. Market.

One of the largest shoe manufacturers in the city, Peters was founded by Henry W. Peters in 1891. In 1911, Peters Shoe Company merged with Roberts, Johnson & Rand to form the International Shoe Company, although the companies continued to maintain their own identities and brands. They manufactured Weatherbird and Red Goose shoes. During World War I, International Shoe Company (including Peters) became the U.S. government’s largest supplier of footwear to the U.S. Army.

Edward and Minnie Seemiller had one son during this decade:

- Edward Michael Seemiller was born on October 5, 1918

1920 – 1929

The 1920 census records provide this scenario:

In 1920, the elder Michael Schuller (74) and his wife Salomé (64) lived at 908 Russell Boulevard, between 9th Street and Menard Street, with their son Mike (32). He was a hat maker, probably employed by the Norris Polk Hat Company mentioned in his draft registration a few years earlier.

In 1920, Alphonse Schuller (42), Emma (38) and their three children, Alice (18), Elmer (16) and Kenneth (10), were living at 1343 Walton Avenue in St. Louis. This census record gives Alphonse’s birth place as Alsace-Lorraine, and not Paris. He was a repairer of automobiles. His son Elmer was employed as a machinist with a mimeograph company. The census was conducted on the 6th and 7th of January, 1920. Although Alice Schuller was enumerated at this address, she had actually married three or four days earlier.

On January 3, 1920, Alice Schuller married Ernest Sagner in St. Louis. (See Ernest Sagner and Alice Schuller)

Ernie and Alice had two children, born during the next six years:

- Betty Lee Sagner, born June 22, 1921

- Alice Anita Sagner, born January 17, 1926

In 1920, Joseph Schuller (38), Margaret (38) and daughter Mildred (16) resided at 1005 Lafayette Avenue in St. Louis. Joseph was an electrician for a picture show, most likely the Majestic Theater, and Mildred was an office clerk for a railroad.

In 1920, Anton Schuller (37) was still an inmate at the City Sanitarium at 5400 Arsenal Street in St. Louis.

In 1920, Minnie (Schuller) Seemiller (30) and Edward Seemiller (27) were living at 2015 South 9th Street in St. Louis with their son Edward Michael Seemiller (3 months). During this decade they had five additional children:

- Virginia Seemiller, born in 1920

- Joseph A. Seemiller, born January 19, 1922

- Leo V. Seemiller, born July 6, 1923

- Raymond Francis Seemiller, born March 19, 1925

- Glennon M. Seemiller, born July 24, 1927

In 1920, Marie (27) and George Roninger (30) were living at 602 Richland Avenue in Effingham, Illinois with their children Louis (5) and Robert (3). George was working as a tire salesman, perhaps still with Firestone.

However, by 1922, they were living in Denver, Colorado where their two daughters were born.

- Mary S. Roninger, born in 1922 in Denver, Colorado

- Dorothy J. Roninger, born in 1924 in Denver, Colorado

This picture, taken in St. Louis in 1926, shows Michael (82) and Salomé Schuller (71) with their son Alphonse Joseph Schuller (29), granddaughter Alice Elizabeth Sagner (25), and great-granddaughter Betty Lee Sagner (5) sitting on Salomé’s lap.

This photo shows the extended Schuller family on the same day, perhaps on the occasion of the baptism of Alice and Ernie Sagner’s second child Alica Anita Sagner. My only clue is that Salome is holding an infant and Alice (seated on her far left, our right) is wearing a corsage.

In the crowd are Michael and Salomé Schuller’s four sons (three on the far left and one on the far right, although I do not know exactly who is who) and two daughters (on either side of their parents). Alphonse is the son on the far left and my guess is that Joseph is on the far right with his wife Margaret, partially hidden. To the right of Alphonse are Tony and Mike, but which is which, I do not know. My guess is that Minnie Seemiller is the woman on the left of her parents and Marie Roniger is the woman on the right.

Included in the photo are the two sons-in-law—George Ronninger (fourth from left, I think) and Edward Seemiller (tall man in back)—and two daughters-in-law—Alphonse’s wife Emma (third from right in the back) and Joseph’s wife Margaret (far right, partially hidden). Of Alphonse and Emma Schuller’s three children, two were married and are with their spouses in this photo—Alice and Ernie Sagner, and Elmer and Audrey Schuller. Alice is on the far right in the middle row and her husband Ernest Sagner is in the back row next to George Roninger. Elmer Schuller is just to the right of Ernest Sagner and his wife Audrey stands behing Alice.

Alphonse and Emma’s younger son Kenneth (17) is on the far left in the front row. Next to him is Ernest and Alice’s daughter Betty Sagner (5). The children at the far right may be Virginia (6) Seemiller and her brother Edward (8). In between are a mixture of Seemiller children—Joseph (4), Leo (3), and Raymond (2)—and Roninger children—Mary (4) and Dorothy (2)—although these four do not fully account for the five I just named. Two must be boys although they are hard to identify by hair and clothing.

1930 – 1939

The 1930 census gives us this scenario:

In 1930, Michael (85) and Salomé (75) were still living at 908 Russell Avenue with their son Mike (44) who was still employed as a hat maker in a hat factory. Michael and Salomé’s grandson, Edward M. Seemiller (11) was living with them. I don’t know the reason for this. His father died four years later of cancer.

In 1930, Alphonse Schuller (53) was living at 5025 Ridge in St. Louis with his wife Emma (48), and his two sons Elmer (26) and Kenneth (20). Alphonse was now listed as an automotive painter, Elmer a house painter, and Kenneth a manager at an insurance company.

In 1930, Joseph Schuller (49) and his wife Margaret (49) were living at 2832 Texas Avenue in St. Louis. Their daughter Mildred was no longer in the house. I have no record of Mildred’s married name. Joseph was still described as an operator of a moving picture machine.

In 1930, there was no record of Anton Schuller (45). I don’t know if he was still a patient in the City Asylum of St. Louis. Perhaps by this time he had been discharged from the hospital, and may have returned home to live with his parents. He was residing at their home when he died in 1941. His death certificate stated that he had worked at odd jobs, usually as a laborer or a truck driver.

In 1930, Mary Roninger (38) was living with her husband George (40) at 411 Emerson Street in Denver, Colorado. They had four children—Louis E. Roninger (15), Robert H. Roninger (13), Mary S. Roninger (8) and Dorothy J. Roninger (6). George was a salesman at a grocery store.

There is no record of Edward and Minnie Seemiller in the 1930 census. We know that their eldest child was living with his grandparents and his uncle Mike. But the rest of the family is unaccounted for. The remaining children—Virginia (10), Joseph (8), Leo (7), Raymond (5), and Glennon (3) are presumably with their parents.

In 1933, Michael and Salome celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary.

On June 7, 1934, Minnie’s husband, Edward Seemiller died of lung cancer at age 41. They were living at 1816 S. 14th Street in St. Louis. His death certificate said that he was a shoeworker. He was buried in Calvary Cemetery at 5239 West Florrisant, St. Louis on June 9. That left Minnie with five young children at home.

The elder Michael Schuller died on April 9, 1936 at his home at age 92 of pneumonia. He was buried on April 11, 1936 in Sts. Peter and Paul Cemetery at 7030 Gravois in St. Louis, section 040. The grave site is near Loughborough Avenue east of Gravois. According to Michael’s death certificate, by 1936 Michael and Salomé Schuller were no longer at 908 Russell Avenue, but were now living at 710 Allen Avenue in St. Louis. It is likely that Anton (Tony) was living with them at this time.

The 1938 Gould’s St. Louis City Directory lists Mrs. Salomé Schuller living at 710 Allen Avenue. Salomé died that year on April 6, 1938 at age 83 of chronic heart and kidney problems which had been diagnosed five years earlier. According to her physician, she was also suffering from senility. The death certificate confirms that her last residence was at 710 Allen Avenue in St. Louis. Salomé was buried on April 9, 1938 alongside Michael in Sts. Peter and Paul Cemetery.

1940 – 1949

The 1940 census provides this scenario of the extended Schuller family:

In 1940, Alphonse Schuller (63) was living at 5028 Wells Avenue with his wife Emma (58) and son Elmer (36). Alfie was working at an automobile garage and Elmer was listed as a laborer. They paid $18 a month rent.

In 1940, Joseph Schuller (58) was living at 2832 Texas Avenue, paying a rent of $15 per month. He was still employed as a projectionist at a theater, but was now widowed. I have no record of when Margaret died, or what became of their daughter Mildred.

In 1940, Michael (Mike) Schuller (53) was living at 710 Allen Avenue. His rent was $14 per month. In the household was his nephew Edward Seemiller (21). Mike was employed as a finisher in a hat factory while Edward—the eldest son of Edward and Minnie Seemiller—was a machinist for a hospital equipment company. Edward Michael Semiller had live with his uncle Mike for at least a decade by 1940.

I have found no 1940 census records for Anton Schuller, for Minnie (Schuller) Seemiller, or for George and Mary (Schuller) Roninger.

Anton Schuller, died on December 28, 1941 at age 57. Five days earlier he had been admitted to the Robert Koch Hospital in St. Louis with pulmonary tuberculosis. The Robert Koch Hospital for Contagious Disease, was located at 4101 Koch Road in Oakville, south of the city of St. Louis.

Like most major American cities in the nineteenth century—especially port cities—St. Louis had repeated problems with infectious diseases. Cholera, yellow fever, leprosy, smallpox and diphtheria were among the diseases to strike the city, leaving tens of thousands dead. By 1910, tuberculosis was responsible for more deaths than all the other infectious diseases combined. To combat the disease, the former Smallpox and Quarantine Hospital was converted and named the Robert Koch Hospital after the German physician who first isolated the tuberculosis bacillus in 1882. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for his tuberculosis findings in 1905 and is considered one of the founders of bacteriology.

Nineteen buildings were constructed by 1939 and an 105-acre farm, post office, railroad stop, housing, and recreational facilities made the hospital almost self-sustaining. By the end of World War II new medications decreased the life-threatening effects of tuberculosis; from the 1950s to 1983 the hospital was used as housing for the indigent elderly.

Anton was buried on December 31, 1941 next to his parents in Sts. Peter and Paul Cemetery.

1950 – 1959

1960 – 1969

Minnie (Schuller) Seemiller died in April 1965 in Missouri at age 76. She is buried in Calvary Cemetery, 5239 West Florrisant, St. Louis.

Alphonse Schuller died on November 4, 1965 in St. Louis at age 88. He is buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery, 2000 Pennsylvania Avenue, Saint Louis. His wife Emma died in 1972.

Joseph Schuller died in September 1966 in St. Louis at age 85.

1970 – 1979

Mike Schuller died in March 1979 in Farmington, Missouri at age 92. Never having married, Mike went to live with his nephew Edward Semiller and his wife Mary Raster in Bonne Terre, Missouri. In his final years, he lived in a nursing home in Farmington, Missouri.

1980 – 1989

Mary (Marie Salome Schuller) Roninger died on April 28, 1982 in Littleton, Colorado at age 90. Her husband George had died in 1971.